This week I took my new school session out to Thing 3’s primary school to test it on Years 5 and 6 – still playing with blue Imagination Playground blocks, but this time the tabletop version which are definitely easier to carry around. Added to these were scraps of fabrics, pipes, string and other loose parts, building on the work we’ve been doing over the summer.

The session, called ‘Think Small’, is an introduction to user-centred design, helping children to understand the iterative design process, work collaboratively and communicate ideas, and finally to work creatively with materials. These are some of the 5Cs of 21st century skills and are the some of the building blocks for learning in the new museum.

We started by thinking about chickens, and what they need to be safe and happy: brainstorming ideas as a class, and then looking at the Eglu. The chickens in question can be seen above – Mabel, Doris and Tome, who belong to one of my colleagues and who were previously commercial egg-laying chickens. We’re in a relatively rural area, so some of the children already had experience of chickens, and were keen to share their ideas. ‘Space to play’ was the most important thing according to one child whose granny is a chicken keeper. We looked then at the Eglu, a chicken house which was designed to make it simpler to keep chickens in garden and which you can see on the left of the picture.

We moved on to talking about what pets we have at home – cats, dogs, guinea pigs, chameleons, geckos, the odd bird and tortoise, hedgehogs – and how they need different environments. I split the classes into four groups, and each team picked a mystery bag with an animal model. As a team they generated a list of things their animal needed which became their ‘client brief’. They were surprised to discover that they wouldn’t be the designing the home for their animal, but had to swap their briefs with another team. Each group then became ‘animal architects’, looking at the brief together and each child designed a home that they thought met that brief. The hardest bit, we discovered, was when the children had to decide which design from their group met the brief best and would be the one put forward to the ‘clients’. Some groups decided quickly, while others needed some support.

The clients gave feedback on the designs and then the architects used the creative kit to build the chosen design, incorporating the feedback, and finally the groups looked at all the designs while the architects talked us through them.

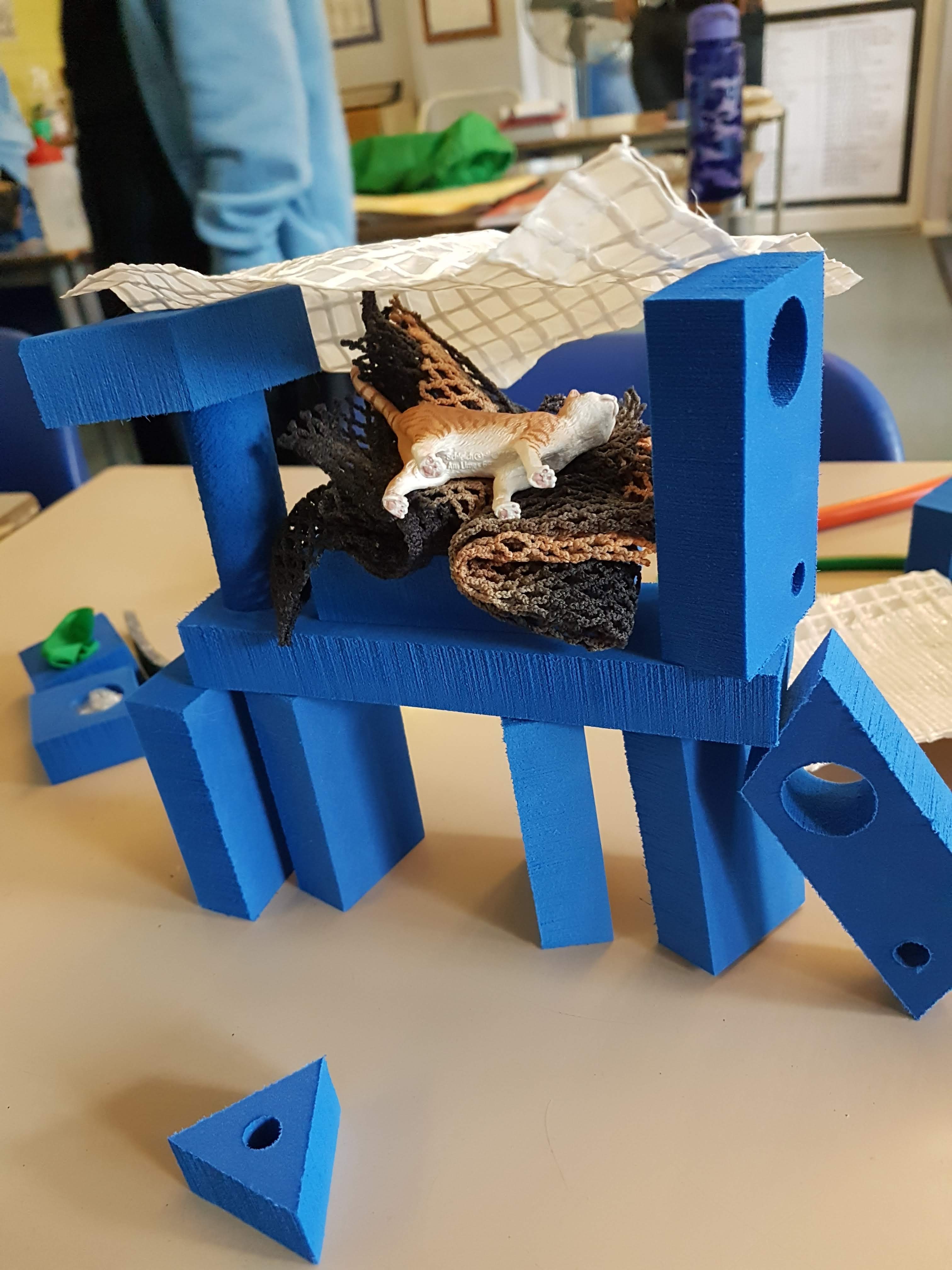

Cat

Hamster

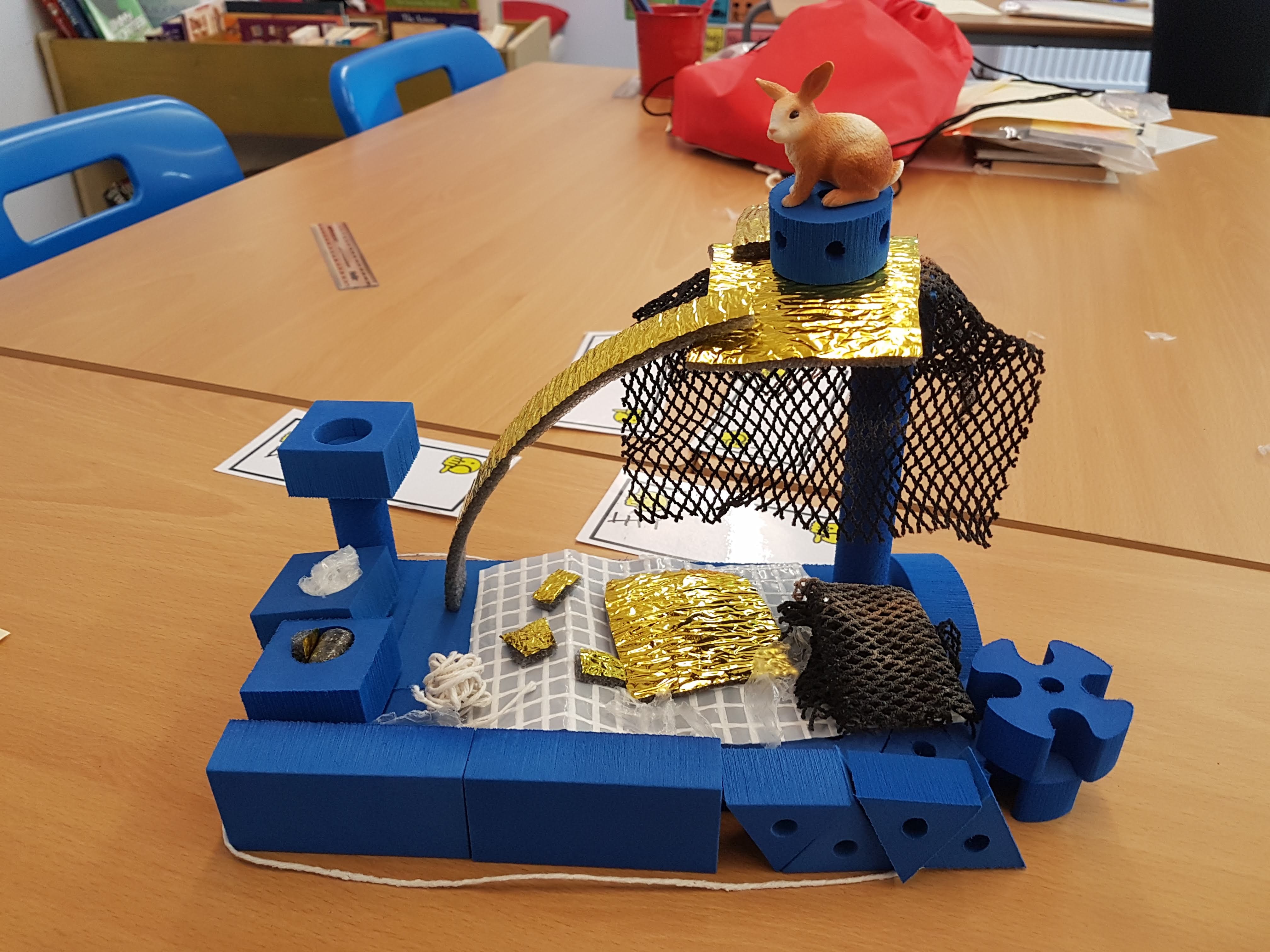

Multi-level rabbit house

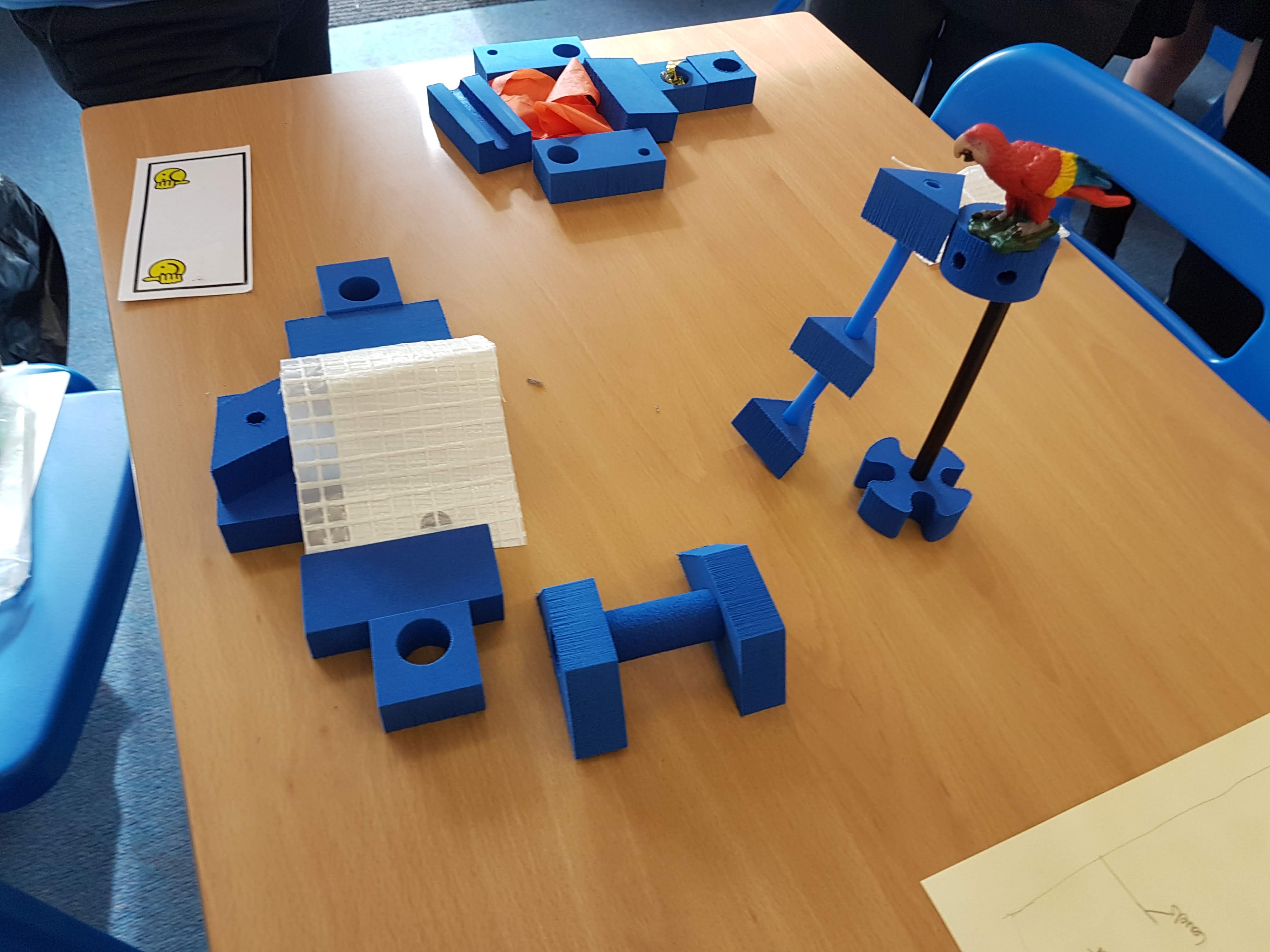

Parrot

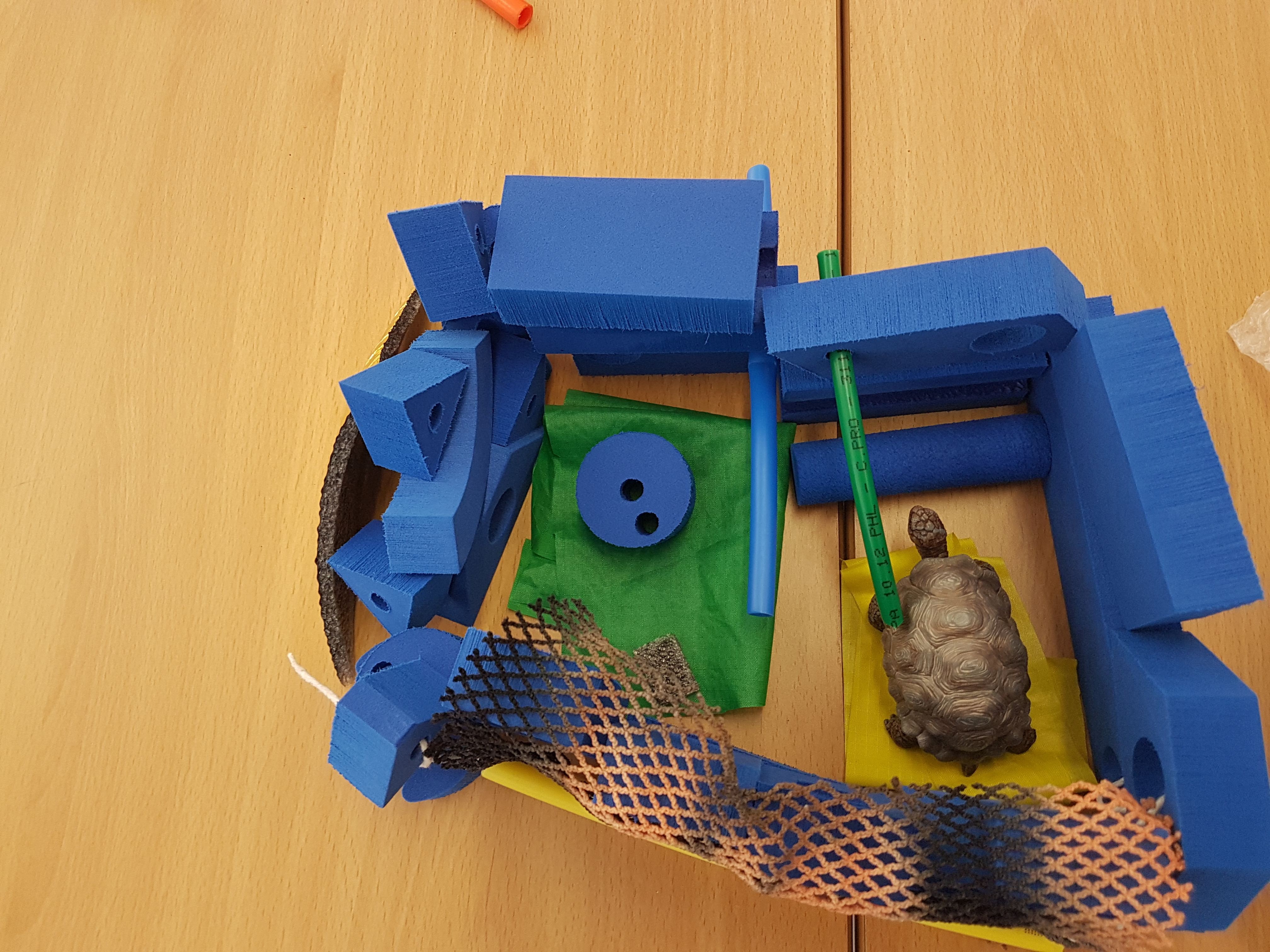

Giant tortoise

Hamster again

The happiest goat ever

Over the four sessions I refined the format and changed some of the timings, and delivering it to the different year groups allowed me to see how it works with different abilities. The classes are quite small, with less than 25 in each which meant four groups in each session was viable. One thing about working with ‘animals’ was that it gave all the children a chance to shine and share prior knowledge from their out-of-school experience rather than reinforcing classroom learning.

I didn’t let them use sellotape or glue, so they had to come up with other solutions to hold objects together or in a particular shape. One boy shone as a project manager, helping his team realise the design he’d created.

Feedback from the children themselves was entertaining: one of them informed me that he didn’t know DT actually involved ‘making things’, another was keen to find out more about making structures stable. Apparently it’s harder to build than to draw, and it needs more brain power than they expected. Building with blocks takes a ‘lot of thinking’. They were surprised when they had to swap their animals to let other people build their ideas; DT is not just on a computer; and it was interesting to think about what other people need. One asked how long it takes to become an architect, so I’m counting that as a win! One wanted to know if I was really Thing 3’s ‘actual mum’.

Thing 3, of course, was mostly just concerned that I didn’t embarrass him too much…

Meanwhile…

Bailey approves of the dragon egg bag

Scraps from the sewing projects I cut out yesterday

As you can see I have some sewing to be getting on with! My first foray into swimwear, for example: a two piece that will be easier to get out of in the winter swimming. The water was 12.6 degrees this morning, so we’re on our way to single figures. There’s also been cross stitch in the evenings, which I’ll share when it’s finished. See you next week…

Kirsty x

What I’ve been reading:

Forests of the Heart/The Onion Girl – Charles de Lint

Comet in Moominland – Tove Jansson (Audible)